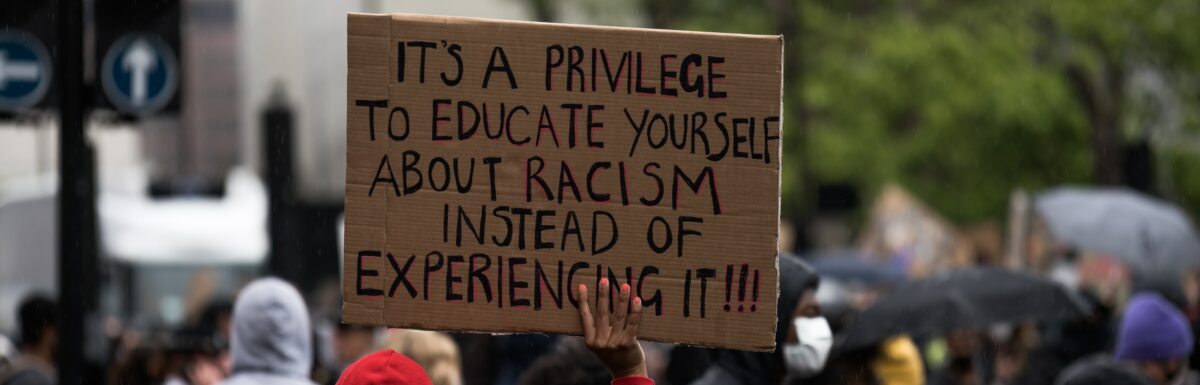

Photo by James Eades on Unsplash

In honor of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day yesterday, I thought I would take a look at one of his most important works. As a white man, my knowledge of the life and work of Dr. King is almost entirely limited to his “I Have a Dream” speech, and I thought that in honor of MLK day, I would take a look at his Letter from Birmingham Jail (text).

Here’s a little summary of the background gleaned from the pixels of Wikipedia:

The Birmingham campaign began on April 3, 1963, with coordinated marches and sit-ins against racism and racial segregation in Birmingham, Alabama. The nonviolent campaign was coordinated by the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR) and King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). On April 10, Circuit Judge W. A. Jenkins Jr. issued a blanket injunction against “parading, demonstrating, boycotting, trespassing and picketing.” Leaders of the campaign announced they would disobey the ruling. On April 12, King was arrested with SCLC activist Ralph Abernathy, ACMHR and SCLC official Fred Shuttlesworth, and other marchers, while thousands of African Americans dressed for Good Friday looked on.

On the same day King was arrested, the local paper published a statement by 8 local white pastors titled, “A Call for Unity” in which they claimed the city was making great progress toward justice and pled the residents of Birmingham to reject the actions of the “agitators” and “outsiders” who had instigated demonstrations in their town. When King read it, he was motivated to write his own open letter in response. Starting on scraps of paper, the letter he composed is a kind of manifesto calling out Christian white “moderates” for being complicit in the continuation of racism and outlining the overall rationale for his nonviolent tactics.

Reading it for the first time today, I want to offer some of my own reflections for my own and your edification.

Initial Reactions

Reading through the letter, I was regularly impressed by King’s ability to express himself, his position, and even the emotions of his perspective without resorting to anything that could be called verbal violence. On the contrary, his words are beautiful, and I was surprised to see in the letter phrases I had heard before without knowing their origin:

Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.

Were I incarcerated by aggressively hostile policemen in a dirty jail cell, I cannot imagine myself to be so eloquent and restrained.

I was also struck by the way King spoke directly to his audience, the local pastors who opposed his presence in Birmingham, with grace and invitation:

I hope this letter finds you strong in the faith. I also hope that circumstances will soon make it possible for me to meet each of you, not as an integrationist or a civil-rights leader but as a fellow clergyman and a Christian brother. Let us all hope that the dark clouds of racial prejudice will soon pass away and the deep fog of misunderstanding will be lifted from our fear drenched communities, and in some not too distant tomorrow the radiant stars of love and brotherhood will shine over our great nation with all their scintillating beauty.

Throughout the letter, King argues for the change he wishes to see, for the church of Jesus Christ to take a glorious role in enacting that change, and for people to do the “creative” work of bringing about those changes in ways that honor God.

Additionally, as I sit here, I think to myself how sad it is that I am 47 years old, have been a full participant in the life of the church since 1975, and am only now beginning to take the words of Dr. King seriously.

A Letter to Me

At the heart of my relationship with Dr. King up until a few years ago is a belief that had been taught to me in many different ways. It’s the belief that slavery was in the past, segregation was in the past, the civil rights movement was in the past, and therefore racism is in the past… except for those rare times when racism shows up embodied in a specific individual. As long as I wasn’t a conscious racist, racism isn’t my responsibility.

There is another belief I had been taught as well. It’s the belief that oppressed people should be patient in their oppression. It isn’t phrased in so many words, but it is implied. We are all taught to be patient, submissive, and long-suffering in our hardships, and therefore, when we see another person who is undergoing hardship, we want to tell that person to also be patient, submissive, and long-suffering. We accept it as a Christian responsibility that the powerful should act on behalf of the powerless, but we also believe the powerless should wait patiently until their liberation comes. We believe that powerful individuals should act individually, and we discourage collective actions such as marches, protests and other forms of activism.

Therefore, I adopted the latent belief that Dr. King and his “activism” was wrong methodology for a noble cause. I could be a fan of his speech at the nation’s capital, but I never understood the marches that came before it. I could support a written letter, but I couldn’t support the protest that got him arrested.

In other words, for most of my life, I have been the kind of person who would have signed the very letter that prompted King’s response. In fact, I read the letter published by those pastors in the newspaper on April 12, 1963, and I am confident I would have signed it.

In other words, King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail was written to me.

Specific Challenges to Me

Moreover, I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states. I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. Never again can we afford to live with the narrow, provincial “outside agitator” idea. Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within its bounds.

I have been guilty of thinking of myself as an insider and other people as outsiders. I never thought of African Americans as outsiders because of the color of their skin, or because of their genealogy. But I have thought of them as outsiders because, from my perspective, they were willfully avoiding the “culture” of the US. I saw the majority white culture as the “proper” culture of the US. I saw the English dialects spoken by African Americans as being literally inferior to the language I spoke. I saw the US as a place where anyone could participate in the culture of success if they simply chose to enter it. And so, I simultaneously thought of the African American community as “outsiders” holding them all at arms length while also blaming them for staying on the “outside” and while also thinking “affirmative action” or “Black History Month” were themselves expressions of racism… keeping the white and black communities separate from each other.

But King reminds me that aside from my identity as a citizen of the U.S. I am a member of the church of Jesus and a member in the image-bearing human race. I am caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, and injustice for anyone is a threat to justice for everyone. My sense that there are “outsiders” should compel me to become a better “inviter” and “integrator” when it’s the right thing to do and to become a better “sojourner” into the life of the outsider when that’s the right thing to do.

You deplore the demonstrations taking place in Birmingham. But your statement, I am sorry to say, fails to express a similar concern for the conditions that brought about the demonstrations. …

… You may well ask: “Why direct action? Why sit ins, marches and so forth? Isn’t negotiation a better path?” You are quite right in calling for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored…

… I have earnestly opposed violent tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth. Just as Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind so that individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half truths to the unfettered realm of creative analysis and objective appraisal, so must we see the need for nonviolent gadflies to create the kind of tension in society that will help men rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood. The purpose of our direct action program is to create a situation so crisis packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation…

…We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed. Frankly, I have yet to engage in a direct action campaign that was “well timed” in the view of those who have not suffered unduly from the disease of segregation. For years now I have heard the word “Wait!” It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity. This “Wait” has almost always meant “Never.” We must come to see, with one of our distinguished jurists, that “justice too long delayed is justice denied.”

I lament that I have far more often judged protesters for their protests than I have judged the oppression they are protesting. Granted, in our world today, as it was true for Dr. King’s day, some protests take shape in ways that are offensive, some take shape in ways that are violent, but some protests, let’s be completely honest, are done in exactly the least offensive way possible. I’m reminded of the criticism that befell many players in the NFL when they decided to protest police violence against black men by kneeling during the national anthem. Before that time, I had never once been in a context where anyone thought “kneeling” was a disgraceful act. Sitting during the national anthem might be considered disgraceful. Turning one’s back on the flag might be considered disgraceful, but taking a knee is a submissive posture. Tim Tebow would do it in the end zone and receive praise, but when Kaepernick did it on the sideline, he was ostracized.

King advocated for “nonviolent direct action” that would constructively create tension and as a result of the tension “open the door to negotiation,” but I and many others are guilty of falsely claiming that the “direct action” was itself wrong or at least poorly timed. We choose to believe in ourselves that if “direct action” were stopped, then negotiation could take place, but King points out that it never took place. Just like Pharaoh did, those who promised negotiation would harden their hearts as soon as the direct action stopped.

Any law that degrades human personality is unjust. All segregation statutes are unjust because segregation distorts the soul and damages the personality. It gives the segregator a false sense of superiority and the segregated a false sense of inferiority…

… Of course, there is nothing new about this kind of civil disobedience. It was evidenced sublimely in the refusal of Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego to obey the laws of Nebuchadnezzar, on the ground that a higher moral law was at stake. It was practiced superbly by the early Christians, who were willing to face hungry lions and the excruciating pain of chopping blocks rather than submit to certain unjust laws of the Roman Empire.

The lesson I have had to learn is that injustice is still injustice regardless of who talks about it. If a powerful person or if a powerful group of people point out injustice with the intention to address it, that’s great! But if an oppressed person points it out with the intent to address it, I should also consider that great. The Christians who opposed the injustice of the Coliseum were the same who were killed in the Coliseum. The friends who opposed the worship of the Babylonian idol were the same who were thrown into the furnace. The real problem is the injustice itself not the messenger or the message and often not even the method.

I need to grow in the recognition that sometimes someone will point out a problem that I don’t think is a problem, and they might employ methods that I don’t like, but that doesn’t give me an excuse to ignore or judge. My responsibility is to listen to them and to understand them. And then, once I understand them, my responsibility just might be to join them in speaking the truth about the injustice and possibly even by direct action.

I must make two honest confessions to you, my Christian and Jewish brothers. First, I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will.…

…I have just received a letter from a white brother in Texas. He writes: “All Christians know that the colored people will receive equal rights eventually, but it is possible that you are in too great a religious hurry. It has taken Christianity almost two thousand years to accomplish what it has. The teachings of Christ take time to come to earth.” …

… Human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability; it comes through the tireless efforts of men willing to be co workers with God, and without this hard work, time itself becomes an ally of the forces of social stagnation. We must use time creatively, in the knowledge that the time is always ripe to do right.…

These words convicted me greatly. I could have been that white brother who wrote King about patience. I have definitely been the white moderate who preferred the “absence of tension” over the “presence of justice,” who agreed with the goal of justice but disagreed with the methods. I have been the person who paternalistically believed I (or my overall tribe) could set the timetable for another man’s liberation. I have been the person of shallow understanding. But what I have not been until recently is a “co worker with God” willing to “use time creatively” because “the time is always ripe to do right.”

These are the words that challenge me to step forward and embrace a new kind of white Christianity. I don’t intend to leave behind any of my biblical convictions. I don’t intend to leave behind any of my theological understandings. But I will no longer allow my idealized notion of the Future Kingdom of God to prevent me from praying toward and working toward its arrival in the here and now.

Of course, the problem with this approach is that although I have changed, the streams in which I swim have not also changed. I might now be able to see the kneeling of an NFL player in a new light, and I might now be able to find affinity, understanding, and agreement with Dr. King, but my own awareness doesn’t mean I am suddenly empowered to be part of the solution. I haven’t been awakened to finally join the mainstream. Rather, I have been awakened to leave it.

And now, from this perspective, Dr. King’s words don’t feel like someone pulling me into a new way of thinking. Rather, I also resonate with his words lamenting the world outside his way of thinking.

… I had hoped that the white moderate would see this need. Perhaps I was too optimistic; perhaps I expected too much. I suppose I should have realized that few members of the oppressor race can understand the deep groans and passionate yearnings of the oppressed race, and still fewer have the vision to see that injustice must be rooted out by strong, persistent and determined action.…

…In the midst of a mighty struggle to rid our nation of racial and economic injustice, I have heard many ministers say: “Those are social issues, with which the gospel has no real concern.” And I have watched many churches commit themselves to a completely other worldly religion which makes a strange, un-Biblical distinction between body and soul, between the sacred and the secular.

I feel like I am beginning to see the need, that I am beginning to see the need for “strong, persistent, and determined action,” that I am beginning to see the synergy between the real gospel and the real social issues. But seeing that way only puts me even more at odds with the majority culture around me.

…In deep disappointment I have wept over the laxity of the church. But be assured that my tears have been tears of love. There can be no deep disappointment where there is not deep love. Yes, I love the church. How could I do otherwise? I am in the rather unique position of being the son, the grandson and the great grandson of preachers. Yes, I see the church as the body of Christ. But, oh! How we have blemished and scarred that body through social neglect and through fear of being nonconformists.

There was a time when the church was very powerful–in the time when the early Christians rejoiced at being deemed worthy to suffer for what they believed. In those days the church was not merely a thermometer that recorded the ideas and principles of popular opinion; it was a thermostat that transformed the mores of society.… By their effort and example they brought an end to such ancient evils as infanticide and gladiatorial contests. Things are different now. So often the contemporary church is a weak, ineffectual voice with an uncertain sound. So often it is an archdefender of the status quo. Far from being disturbed by the presence of the church, the power structure of the average community is consoled by the church’s silent–and often even vocal–sanction of things as they are.…

…But the judgment of God is upon the church as never before. If today’s church does not recapture the sacrificial spirit of the early church, it will lose its authenticity, forfeit the loyalty of millions, and be dismissed as an irrelevant social club with no meaning for the twentieth century. Every day I meet young people whose disappointment with the church has turned into outright disgust.

This is perhaps my greatest concern at these times. Yes, I have a newfound passion for the cause of social justice in the world, but truth be told, I have an even greater passion for the integrity and testimony of the church. I rest heavily on Jesus’ promise that the gates of Hades would not overcome his church, but I also recognize that he made no such promise about the version of the church we have in this country. As Jesus told the church at Laodicea, he has no problem ridding himself of certain versions of the church, and my fear is that we are next. My fear is that the church to be found in the US is as weak and delusional as that of the Laodiceans, as lukewarm as they, as shut off from the real presence of Christ as they, and that it will remain so until Jesus finally spits us out.

Dr. King was not as defeated as I feel these days regarding the church in America. Rather, near the end of his letter he gave this extremely hopeful statement:

But even if the church does not come to the aid of justice, I have no despair about the future. I have no fear about the outcome of our struggle in Birmingham, even if our motives are at present misunderstood. We will reach the goal of freedom in Birmingham and all over the nation, because the goal of America is freedom. Abused and scorned though we may be, our destiny is tied up with America’s destiny. Before the pilgrims landed at Plymouth, we were here. Before the pen of Jefferson etched the majestic words of the Declaration of Independence across the pages of history, we were here. For more than two centuries our forebears labored in this country without wages; they made cotton king; they built the homes of their masters while suffering gross injustice and shameful humiliation -and yet out of a bottomless vitality they continued to thrive and develop. If the inexpressible cruelties of slavery could not stop us, the opposition we now face will surely fail. We will win our freedom because the sacred heritage of our nation and the eternal will of God are embodied in our echoing demands.

However, despite the hopeful tone of this paragraph, I can’t help but notice where his hope is to be found. Did you see it? His hope is in the eternal will of God, and his hope is in the “sacred heritage of our nation,” but it is not in the church. It saddens me that King can find hope in the will of God, and he can find hope in the vague idea of America’s destiny, but he doesn’t have that same hope in the people of God who call themselves the church.

Little Has Changed

Reading through Dr. King’s words, and thinking through these things today, I realize that the relationship of the “moderate” white church to the cause of racial justice hasn’t changed much throughout my lifetime. In my experience, no church I have ever been in even verbalized a desire to “come to the aid of justice.” I have been in churches that had goals of being a “multicultural” ministry, but I have never been in a church with a white pastor that was also actively moving the wheels of justice forward or that would even acknowledge that racial injustice persists to this day.

Sure, there are some who would say the real problems of racism are in our past, but statistics and data do not agree with that perspective, and regardless, that was the same claim made by the 8 pastors who signed the statement prompting King’s letter in the first place. Racism is with us still because we haven’t ever actually admitted it was with us.

Nevertheless, little by little, some things have changed. For one, I have changed, or at least, I am changing.

In the past few years, a combination of intentional friendships with African Americans, a number of difficult conversations, an assortment of books and podcasts, and a willingness to learn has definitely changed me. People in my cultural frame often make fun of “woke” culture, but I on the other hand can actually describe my journey as a sort of awakening. I do believe my eyes have been opened to something I had previously ignored.

The only question remaining for me is these two ongoing questions: Where else do I need to grow? and What can I do?

Both of those questions are ones I’m not answering for myself. Rather, I keep asking others, particularly my African American friends, to help me answer them.

Dr. King’s voice is a precious one in that regard.